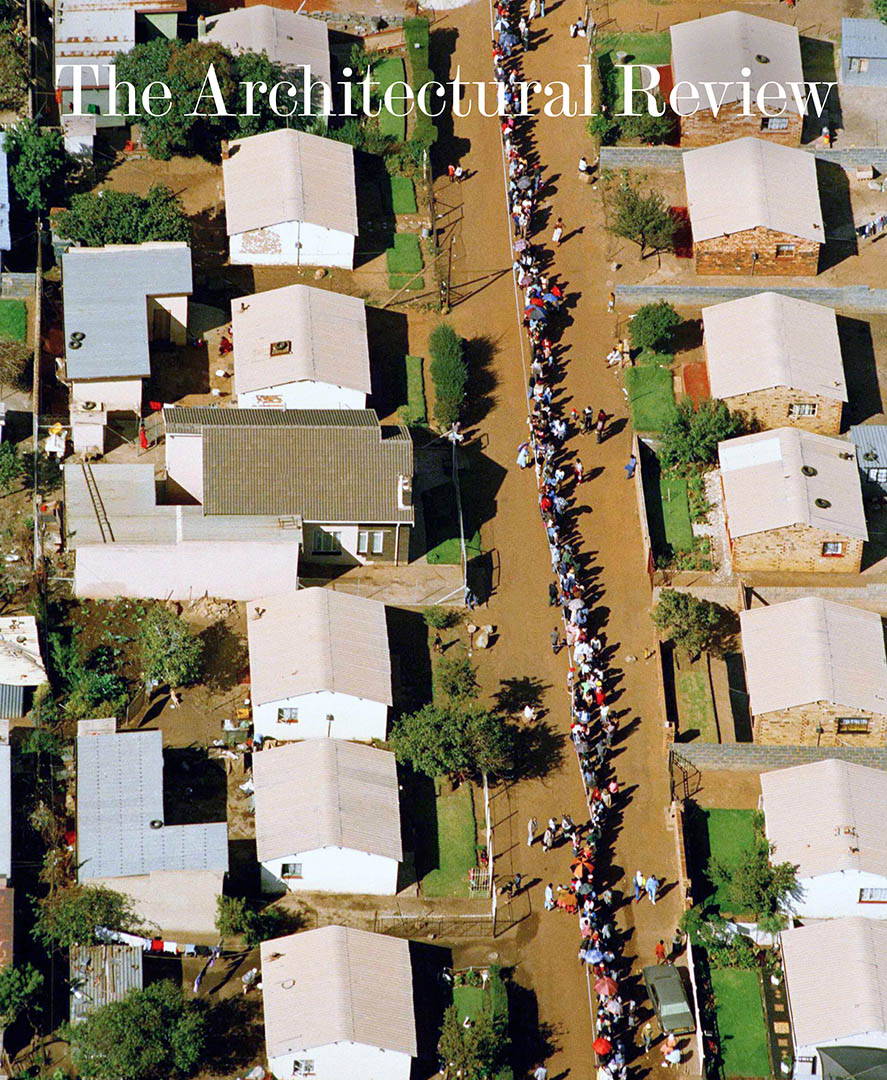

Namibia is one of the youngest democracies in Africa. How to unite as a nation when the architecture of German colonialism and the built realities of Apartheid continues to divide, I ask in an essay for the ‘democracy’ issue of ‘the architectural review’ magazine.

A fresh breeze blows down Independence Avenue. In Windhoek-Central people gather in parks and cafes, listening to live music in bars or poetry readings. The country only gained independence from South Africa’s apartheid regime in 1990. A young, educated generation – 2.1 million of the country’s 3 million people are under 35 – is taking over and flocking to the city.

A sense of new beginnings meets built realities: German colonialism has permeated much of the infrastructure. It still shapes the cityscape, leaving traces in buildings, monuments and street names. The German genocide of the Nama and Ovaherero committed during a war of annihilation between 1904 and 1908 lives on to this day in many family stories that tell of land theft, exploitation and violence.

The Alte Feste, a fortress built by German colonial troops in 1890, rises up on the central hill in Windhoek. Next to the military fort, the Germans built one of their first concentration camps in 1904. The fort was seized by South African occupying forces in 1915, and under South African rule Windhoek High School was built 1917 and relocated on the site of the concentration camp in 1923, where it still stands today. According to research by the multidisciplinary group Forensic Architecture, the exact area where the camp once stood is now a car park and sports field for the high school. Where Nama and Ovaherero people were once enslaved labourers, young people in uniform now sit in classrooms. Rugby is played on the field next door. Nothing marks the camp. […]